by Scott Martin Photography | Mar 22, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Educational, Raptors, Wildlife

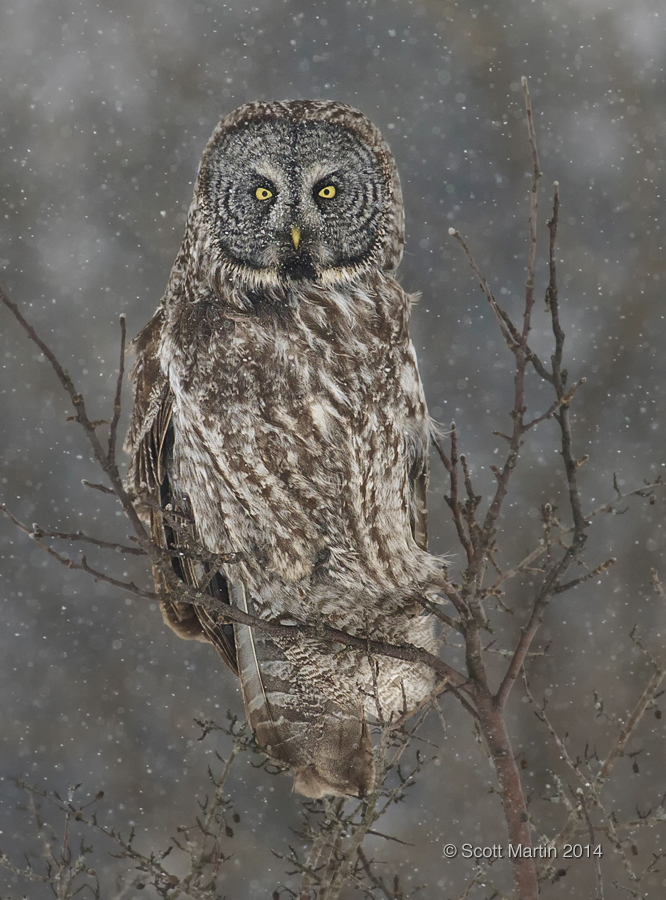

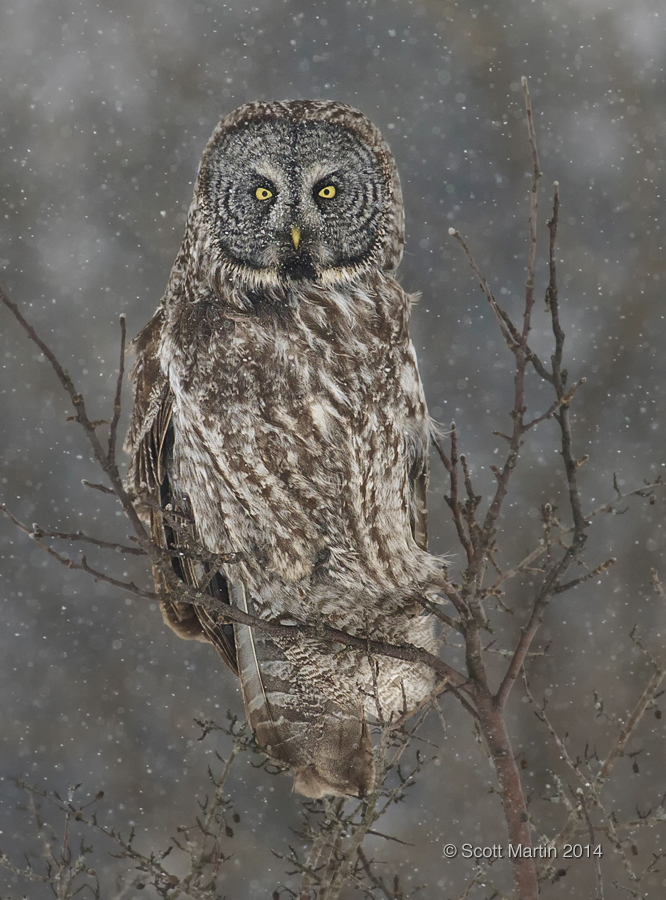

Before people start questioning the title of today’s blog, please let me clarify that the Great Gray Owl is the world’s longest owl with a recorded body length of up to 33″ (and a wing span of over 60″). You may want to think of this a deceptive length as it is the large head and fluffy feathers (better insulation) that are hiding a proportionally smaller body, such that many other owl species are heavier than the Great Gray. Anyway, the take away is that the Great Gray Owl is a very large and majestic looking bird, which I believe is captured in this first image which is also my favourite owl image from this past winter.

The Great Gray Owl is a northern owl that breeds in the far north regions of North America, Europe and Asia and although a nomadic bird, they do not migrate. As non-migratory birds, they are sometimes seen farther south than normal in years when food sources in the north are scarce and competition for food forces some birds to head south until they find more abundant food that they can successfully compete for. Their diet is 80% small rodents (voles and mice) and 20% from alternate prey sources including small birds and ducks.

This winter we were fortunate have a Great Gray Owl take up residence just north of Brooklin Ontario, not more than a ten minute drive from our house, which provided plenty of opportunities to photograph this celebrity visitor. And a celebrity it was, attracting birders and photographers from many miles away on a daily basis.

You probably noticed the image above was shot while it was snowing, which certainly adds to the photograph and serves as a reminder get out there when it’s snowing (or raining) as some of the best images are obtained in inclement weather. When it’s snowing you do need to take some time to think about how the snow will affect the image and how you wish the snow to appear in the image, just as you would for any of the elements that occupy the frame. Personally, I prefer the snow to be either frozen in the frame (pun intended :)) and appearing as round flakes, or heavily blurred to illustrate the wind and provide that winter storm look. An exposure time that allows just a little bit of movement in the flakes creates an unappealing optic with the snow appearing as a distractive cloud of gnats. The first image above was taken at 1/2000 sec, which preserved the round snow flakes. This next image was taken at 1/500 sec, allowing some motion in the snow flakes and creating that unpleasant fly look which you want to avoid.

A much slower exposure of 1/30 sec was used for the next image which fully blurs the snow, but in a way that contributes to the success of the image by giving the feeling of the wind driving the snow.

The challenge with slow shutter speeds is causing out of focus results either from camera shake or object movement during the exposure. So even using a lens with image stabilization, mounted on a tripod, I took at least a dozen shots to finally get one with the owl in sharp focus.

The next time you have the opportunity to take your camera out into the snow, don’t be afraid to do it, but always think about how the snow will impact your images and experiment with different shutter speeds until you create the desired effect. Also, when photographing birds, remember that slow shutter speeds are always the last thing you experiment with and don’t forget to set your exposures back to high shutter speeds as soon as you get the shot you want. Nothing is more frustrating than missing an owl launch from its perch while you have your camera dialled in at 1/30 sec! Fortunately I was back at 1/1600 sec for this next capture.

When shooting in less than ideal weather, the light is often quite nondescript producing the white/grey back grounds that typically are not visually appealing. However always try to use the light to your advantage. The over cast lighting reduces the natural contrast between the light & dark areas in the frame which is sometimes referred to as high key lighting (especially when there are no fully black shadows in the image). If you don’t like the high key look you can always add blacks and contrast during post processing which is what I did in these next few images.

Images like these with an all white back ground are perfect to use as title slides in any presentations you may be doing.

Bird photographers are usually upset when they cut off parts of the bird, but sometimes these accidents work out well. This next image is almost completely un-cropped in post processing (about 15% of the right side of the image was cropped). It just so happened that the owl landed on a perch very close to me and the 400mm lens was ‘too much lens’ so the owl more than filled the frame. The image does capture the concentration, intensity and focus of the owl securing the landing position on the perch it had chosen. Although accidental, the resulting image became a ‘keeper’.

This next image is a crop of a missed launch image taken as the owl took off from its perch and I cut off the head of the bird. The intent then became to crop the image to isolate the legs and tail and convey the great power required for the owl to propel itself into the air. I don’t believe this image works as well as the previous one to convey the message, but the point is, don’t always delete your ‘mistakes’ before looking at them closely to see if perhaps there is a picture within the picture that can be used for an intent other than originally planned. They don’t always work (as shown in these two images) but when they do, it is a pleasant surprise.

The last sequence of images in today’s post illustrates one of the typical hunting methods of the Great Gray Owl.

Great Gray Owls use sound and hearing as the primary sense required to effectively hunt for food and although they do have incredible visual acuity, they are most active feeding before dawn and after dusk when hearing is more important than sight. Their large facial disks act as parabolic reflectors amplifying and concentrating sounds on their asymmetrically located ears allowing them to accurately locate prey, up to two feet below the surface of the snow. This is truly amazing when you stop to think about it.

Listening intently to locate the prey.

Hopeful success.

The images posted in today’s blog were taken with two different gear combinations, a Canon 5D MkIII with a 500mm lens and a Canon 1D MkIII with a 400mm lens.

It is always a pleasure to spend time out taking pictures, however it’s even more special when you get to do so with great friends and on the day we took these pictures Deb & I were joined by Arni & Dianne who made the trek south from Orillia to see the Great Gray Owl. You can see Arni’s shots of the Great Gray Owl posted on his blog.

I trust you enjoyed seeing these Great Gray Owl images and as always, your questions, comments and critiques are much appreciated.

by Scott Martin Photography | Mar 3, 2014 | Birds, Blog, Educational, Raptors, Shore Birds & Waterfowl, Wildlife

This winter has been unusually long and cold with our province blanketed in snow to depths that I can’t recall since growing up in the Ottawa Valley. Fortunately it has also been a pretty good winter for bird photography, especially regarding Snowy Owls for which this year has been an irruption year. An irruption year occurs infrequently and although there are different theories as to exactly what causes a particular species of bird to head farther south in greater numbers than usual, it most likely revolves around competition for food. In winters when food supplies are scarce or years that bird populations are large, the competition for food forces the disadvantaged (the young, very old or infirm) south in search of more easily obtained food. This is why Snowy Owls found significantly south of their normal range are usually young first year birds. After wintering farther south than normal and eating well, the owls head back to the Arctic in February or March for the next nesting season. The Snowy Owl irruption experienced this year has been the largest in 40-50 years and a Snowy Owl actually made it to Jacksonville Florida, which is incredible for a non migratory Arctic bird! When Snowy Owls are displaced southward they seek areas to stay that remind them of the tundra they are accustomed to, so you often find them in open areas such as farmers fields.

Their predilection for farmer’s fields results in the classic images we see of Snowy Owls perched on fence posts.

Although not the biggest or heaviest owl, the Snowy is still an impressive bird about 2.5′ high with a wingspan of five feet and weighing up to six pounds. Only in flight can you get an appreciation for their wingspan.

Deb and I were photographing a Snowy Owl last month when a snow squall moved through the area and presented us with the opportunity to get a unique image that I hope illustrates the type of environment the Snowy Owl is used to in the high Arctic.

The winter months in Ontario are also a great time to see a number of northern diving ducks which winter on the Great Lakes. In fact the introduction of Zebra Mussels in 1988 to Lake St. Claire and Lake Erie from a European freighter and their subsequent infestation of the Great Lakes (particularly Erie & Ontario) has provided a dubious but plentiful food source for the ducks. Consequently in recent years we have seen more varieties of ducks as they change their historic migration patterns to include the Great Lakes and the Zebra Mussel buffet they provide.

On a recent tour of Southern Ontario looking for winter owls and ducks with my good friend Arni, we were able see a number of different duck species as well as four different owls species. Arni is a birder and photographer second to none and you will enjoy following this link to his website. These next images of ducks were taken on our tour and although it was a dreary day the poor light did not stop Arni and me from enjoying both the birding and the photography as well.

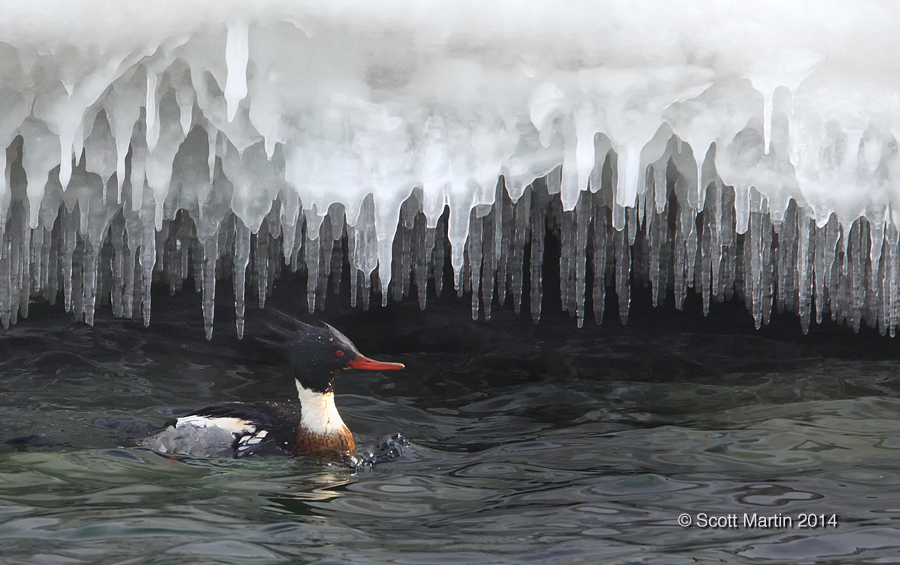

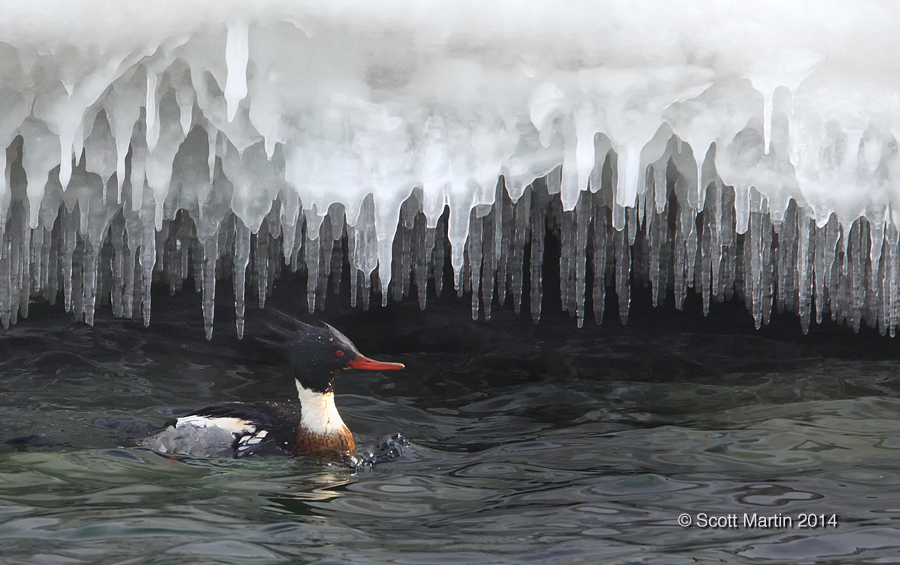

First up is the Red Breasted Merganser, the rarest of the three Mergansers in North America, and a new bird for me to photograph. If you want to see the other two Merganser species (Common Merganser and Hooded Merganser), they can be found in the Waterfowl Gallery.

Baby it cold outside!

.

This next image is of Red-headed ducks, another relatively new and unusual visitor to the Great Lakes to feast on the Zebra Mussel. The Red-headed duck is an interesting species as it never builds its own nest, choosing instead to lay its eggs in the nests of other duck species and even in the nests of American Bitterns and Northern Harriers. Apparently they aren’t into parenting!

The White-winged Scoter is another Arctic breeding duck that is found through North America, Europe and Asia. It heads south in the winter months and their numbers have been increasing on the Great Lakes over the past few years. They are a large dark brown to black bird with distinctive white markings around the eyes and speculum. The next two pictures are of the White-winged Scoter, the male first followed by the female and both with a clump of Zebra Mussels.

.

Since the inadvertent introduction of Zebra Mussels to the Great Lakes, they have overtaken Lake St. Claire, Erie and Ontario, largely due to their prolific reproduction with relatively few predators eating into their numbers. A Zebra Mussel has a life span of approximately five years and females begin having young at about six weeks of age, producing one million offspring annually. The crayfish, one of the mussel’s main predators, consumes about 40,000 per year. The Zebra Mussel filters approximately one gallon of water every day, removing nutrients for itself. Unfortunately the toxins in the water, of which there are many, accumulate in the mussel and there in lies the problem for the birds who consume the muscles and with them the toxins and contaminants from the lakes, and in a concentrated form. The health effects on the birds is not yet known, however it is a huge concern to conservationists and researchers who are investigating the effects of the muscles on birds. It is already suspected that avian botulism is transferred via the Zebra Mussel and this kills many birds annually.

Shifting gears back to owls, the first of four owl species Arni and I saw was the Eastern Screech Owl, which was a new species for me to photograph. The Eastern Screech Owl is a strictly nocturnal bird that hunts at night and then finds its roost in a tree cavity where it spends the daylight hours sleeping. They are a small bird about 10″ high with a wingspan of 18-24″. Most Eastern Screech Owls are grey in colour, however about 10% of these owls are a rufus or red morph and it was a pleasure for us to have found this rarer colour of the Eastern Screech Owl.

After leaving the Screech Owl we were able to find a Snowy Owl however he was too far away to get any blog worthy images of so we left and arrived at another location where we found a Short-eared Owl hunting over a large area around a quarry. Although we set up out tripods and gear, the Short-eared Owl didn’t fly close by, so as with the Snowy Owl, we struck out getting any shots. The disappointment was short-lived as after arriving at a conservation area on the shores of Lake Ontario we found a large coniferous tree that was home for the day to six Long-eared Owls. It was the largest number of owls I’d ever seen in the same tree.

The Long-eared Owl is a slender owl with long ears, large bright yellow eyes and huge eye discs that give it a characteristic look that is hard to miss.

It was also a pleasant surprise to catch one in flight.

Many photographers put their camera gear away for the winter, but as long as you dress for the occasion and make sure your batteries are fully charged, cold weather photography is a lot of fun and often affords the pleasure of seeing birds that you simply can not see in Ontario at any other time of the year.

We’ve been privileged this winter to also have photographed two other species of owl, the Great Gray Owl which the world’s largest owl and the Short-eared Owl which is arguably the prettiest of the owls. They will form the subject matter for the next two blog posts before retuning to our European tour.

Follow Scott Martin Photography