This winter has been unusually long and cold with our province blanketed in snow to depths that I can’t recall since growing up in the Ottawa Valley. Fortunately it has also been a pretty good winter for bird photography, especially regarding Snowy Owls for which this year has been an irruption year. An irruption year occurs infrequently and although there are different theories as to exactly what causes a particular species of bird to head farther south in greater numbers than usual, it most likely revolves around competition for food. In winters when food supplies are scarce or years that bird populations are large, the competition for food forces the disadvantaged (the young, very old or infirm) south in search of more easily obtained food. This is why Snowy Owls found significantly south of their normal range are usually young first year birds. After wintering farther south than normal and eating well, the owls head back to the Arctic in February or March for the next nesting season. The Snowy Owl irruption experienced this year has been the largest in 40-50 years and a Snowy Owl actually made it to Jacksonville Florida, which is incredible for a non migratory Arctic bird! When Snowy Owls are displaced southward they seek areas to stay that remind them of the tundra they are accustomed to, so you often find them in open areas such as farmers fields.

Their predilection for farmer’s fields results in the classic images we see of Snowy Owls perched on fence posts.

Although not the biggest or heaviest owl, the Snowy is still an impressive bird about 2.5′ high with a wingspan of five feet and weighing up to six pounds. Only in flight can you get an appreciation for their wingspan.

Deb and I were photographing a Snowy Owl last month when a snow squall moved through the area and presented us with the opportunity to get a unique image that I hope illustrates the type of environment the Snowy Owl is used to in the high Arctic.

The winter months in Ontario are also a great time to see a number of northern diving ducks which winter on the Great Lakes. In fact the introduction of Zebra Mussels in 1988 to Lake St. Claire and Lake Erie from a European freighter and their subsequent infestation of the Great Lakes (particularly Erie & Ontario) has provided a dubious but plentiful food source for the ducks. Consequently in recent years we have seen more varieties of ducks as they change their historic migration patterns to include the Great Lakes and the Zebra Mussel buffet they provide.

On a recent tour of Southern Ontario looking for winter owls and ducks with my good friend Arni, we were able see a number of different duck species as well as four different owls species. Arni is a birder and photographer second to none and you will enjoy following this link to his website. These next images of ducks were taken on our tour and although it was a dreary day the poor light did not stop Arni and me from enjoying both the birding and the photography as well.

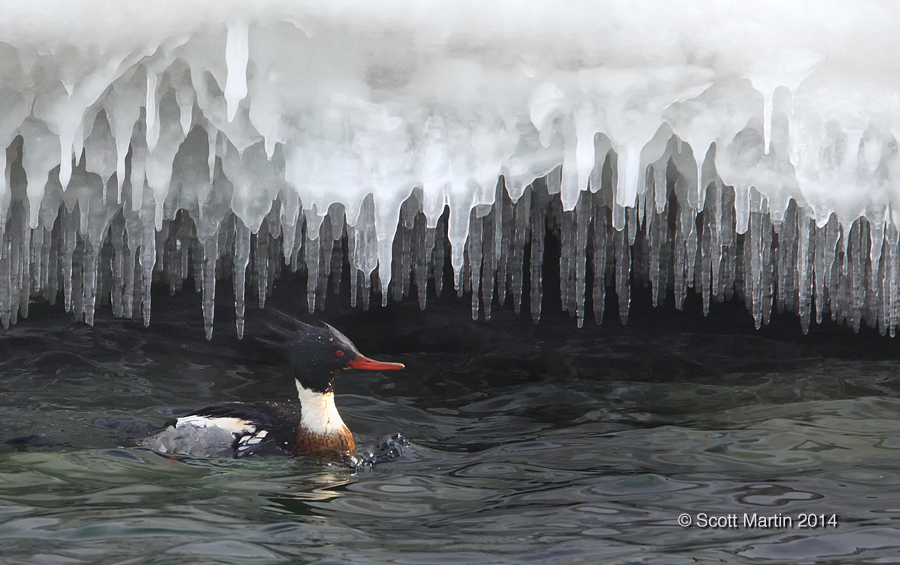

First up is the Red Breasted Merganser, the rarest of the three Mergansers in North America, and a new bird for me to photograph. If you want to see the other two Merganser species (Common Merganser and Hooded Merganser), they can be found in the Waterfowl Gallery.

Baby it cold outside!

.

This next image is of Red-headed ducks, another relatively new and unusual visitor to the Great Lakes to feast on the Zebra Mussel. The Red-headed duck is an interesting species as it never builds its own nest, choosing instead to lay its eggs in the nests of other duck species and even in the nests of American Bitterns and Northern Harriers. Apparently they aren’t into parenting!

The White-winged Scoter is another Arctic breeding duck that is found through North America, Europe and Asia. It heads south in the winter months and their numbers have been increasing on the Great Lakes over the past few years. They are a large dark brown to black bird with distinctive white markings around the eyes and speculum. The next two pictures are of the White-winged Scoter, the male first followed by the female and both with a clump of Zebra Mussels.

.

Since the inadvertent introduction of Zebra Mussels to the Great Lakes, they have overtaken Lake St. Claire, Erie and Ontario, largely due to their prolific reproduction with relatively few predators eating into their numbers. A Zebra Mussel has a life span of approximately five years and females begin having young at about six weeks of age, producing one million offspring annually. The crayfish, one of the mussel’s main predators, consumes about 40,000 per year. The Zebra Mussel filters approximately one gallon of water every day, removing nutrients for itself. Unfortunately the toxins in the water, of which there are many, accumulate in the mussel and there in lies the problem for the birds who consume the muscles and with them the toxins and contaminants from the lakes, and in a concentrated form. The health effects on the birds is not yet known, however it is a huge concern to conservationists and researchers who are investigating the effects of the muscles on birds. It is already suspected that avian botulism is transferred via the Zebra Mussel and this kills many birds annually.

Shifting gears back to owls, the first of four owl species Arni and I saw was the Eastern Screech Owl, which was a new species for me to photograph. The Eastern Screech Owl is a strictly nocturnal bird that hunts at night and then finds its roost in a tree cavity where it spends the daylight hours sleeping. They are a small bird about 10″ high with a wingspan of 18-24″. Most Eastern Screech Owls are grey in colour, however about 10% of these owls are a rufus or red morph and it was a pleasure for us to have found this rarer colour of the Eastern Screech Owl.

After leaving the Screech Owl we were able to find a Snowy Owl however he was too far away to get any blog worthy images of so we left and arrived at another location where we found a Short-eared Owl hunting over a large area around a quarry. Although we set up out tripods and gear, the Short-eared Owl didn’t fly close by, so as with the Snowy Owl, we struck out getting any shots. The disappointment was short-lived as after arriving at a conservation area on the shores of Lake Ontario we found a large coniferous tree that was home for the day to six Long-eared Owls. It was the largest number of owls I’d ever seen in the same tree.

The Long-eared Owl is a slender owl with long ears, large bright yellow eyes and huge eye discs that give it a characteristic look that is hard to miss.

It was also a pleasant surprise to catch one in flight.

Many photographers put their camera gear away for the winter, but as long as you dress for the occasion and make sure your batteries are fully charged, cold weather photography is a lot of fun and often affords the pleasure of seeing birds that you simply can not see in Ontario at any other time of the year.

We’ve been privileged this winter to also have photographed two other species of owl, the Great Gray Owl which the world’s largest owl and the Short-eared Owl which is arguably the prettiest of the owls. They will form the subject matter for the next two blog posts before retuning to our European tour.

What a fantastic read Scott. Learnt so much about these birds here and of course thoroughly enjoyed seeing the shots. Really enjoyed this post

Thanks Rob, your kind comments are always much appreciated.

Scott,

Great photos and very educational!

Thanks Don, its been a good winter for birds!

Another superb post Scott. While all the images are note-worthy I am particularly fond of the Long-eared closeup and is a shining example of the capabilities of the full-frame 5DMKIII for bird photography. The facts on the Zebra Mussel are truly frightening.

Thanks Arni and you are correct about the 5D MkIII. The Zebra Mussels have increased the water clarity in Lake Erie from 6″ to over 3′ since 1988, but the resulting increased penetration of the sun has caused severe algae proliferation which is also creating havoc in the lakes. There is nothing good to tell about the Zebra Mussel.